Discover the methods and tools used by the Flatliners sound team to guide the viewer between worlds.

What happens after you die?

In the film Flatliners, now in theaters, a group of medical students seek the answer to that question by intentionally stopping their hearts for a specified amount of time. Their near-death experiences are extraordinary but quickly turn dark when elements from the afterlife follow them back into their everyday lives.

You might be familiar with the Flatliners director Niels Arden Oplev from his Swedish film The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009), which came out years before director David Fincher’s version in 2011. Oplev’s American theatrical debut was Dead Man Down (2013), a New York City-based crime thriller starring Colin Farrell and Noomi Rapace.

Contributing to the sound of Dead Man Down was sound effects editor David Esparza, who joined Oplev’s sound team on Flatliners as a sound designer/re-recording mixer on the effects/Foley/backgrounds. Esparza and long-time collaborator supervising sound editor Mandell Winter handled sound editorial at Sony Pictures Post Production in Culver City, CA before joining dialogue/music re-recording mixer David Giammarco for the final mix in Sony’s Kim Novak Theater.

Here, Winter and Esparza share insight on how they designed and mixed the sound for Flatliners.

Images courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Mandell and David, you have worked together on over 20 films. How did this partnership come about?

Mandell Winter: We started working together on a film called Southland Tales (2006). David was supervising and I came on to cut the Foley. And we’ve worked together in various capacities over the years.

David Esparza: After Southland Tales, we worked together freelancing. I’d say our first full, real collaboration was The Mechanic (2011). We work really well together with similar work ethic and passion for the craft. We have skill sets that complement each other. So we never looked back after that really.

When you share the sound supervising duties, is there a specific way that you like to split it up?

Winter: We split it up into dialogue and design/effects. David will handle the design/effects side and I’ll handle the dialogue and more of the administrative tasks.

Mandell Winter & David Esparza

Mandell Winter & David EsparzaHow did you get involved with Flatliners?

Winter: David worked on the film Dead Man Down with Director Niels Arden Oplev and Peter Schultz, who is Niels' long time sound collaborator from Denmark. Peter started the project, coming out here and working on it with us but the schedule extended and he was unable to continue on it after the first couple temp mixes.

What was Dir. Oplev’s plan for using sound to help tell this story?

Esparza: In the early conversations, he wanted us to look at making the contrast between the natural world and the supernatural world. Niels is into creating a dynamic track to help create moods. He also uses sound in a more practical manner to help define the various spaces in the film, for example, the sound of the ICU room versus the hospital.

In addition, there’s the idea of creating certain sound motifs for each character, dependent upon their experience in the film — for the flatlining experience and for when they come back as well, and for the psychological torment that they endure and go through in the rest of the film.

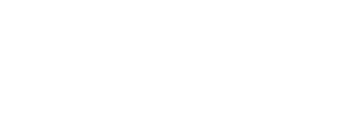

Jamie (James Norton), Courtney (Ellen Page) Ray (Diego Luna), and Marlo (Nina Dobrev)

Jamie (James Norton), Courtney (Ellen Page) Ray (Diego Luna), and Marlo (Nina Dobrev)What were the director’s initial focus points for sound?

Esparza: The first thing we saw was the MRI machine. When a character flatlines, the others are doing brain scans to search for an answer to what the brain does upon death. They are trying to determine what the afterlife truly is.

The MRI machine initially was supposed to be a big sonic player, sort of the engine that drives the flatlining sequences. So that was one of the initial sounds that was tackled. Peter Schultz had taken the sound of an MRI machine that was supplied to us by the picture editor Tom Elkins and he built on that.

“Respect the work that your picture editor has done to the track. Part of our job is not reinventing the wheel, but making the wheel bigger and better.”

How did that initial sound evolve into what is in the film?

Esparza: It was a very rhythmic sounding machine and so Peter took that and enhanced it a bit by giving it some cool pulsing undertones that played in rhythm with the machine as well as adding perspectives to it.

Initially, that sound was supposed to be the main engine to the whole sequence. So much so that the initial score for the flatlining sequences was done in time and in a similar pitch to the sound of the MRI machine. But, interestingly enough, in the end as the film came together, the idea of the MRI machine being the driving engine sort of devolved a bit. It became less of a player as the scene became more music driven. They even ended up changing the score and the way the score worked in the sequences. So once the MRI machine is established, it became less of a player in the overall mix.

In the film, the MRI machine is so visually represented in the room where they are having the flatlining experiences that we could take away the sound when we needed to and bring it back whenever the music wasn’t driving things. The MRI machine is always there, very prominent visually, and that allowed us to sneak away the sound and bring it back when necessary.

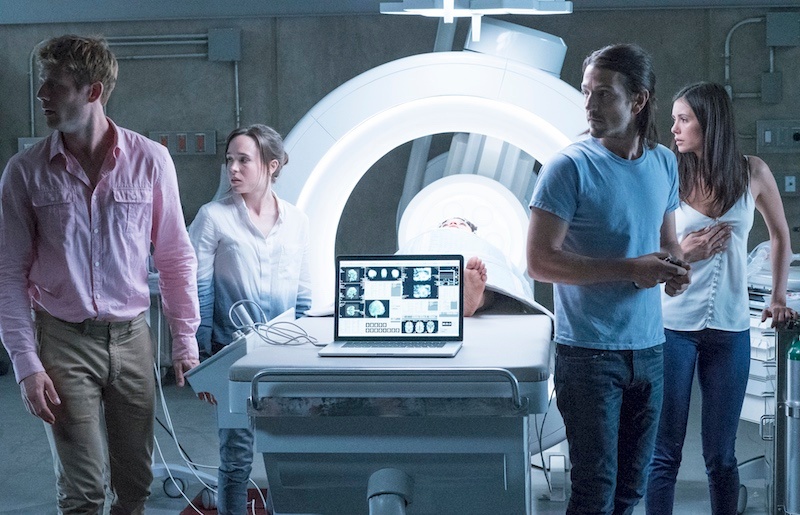

Dr. Barry Wolfson (Kiefer Sutherland)

Dr. Barry Wolfson (Kiefer Sutherland)“Dolby Atmos allowed us to play up both sides. We used the Atmos in the flatlines and altered realities, and then used a traditional surround mix in the natural world.”

What does flatlining sound like? Does it sound different for each character?

Winter: I would say that it’s character-driven, based on their personal experiences. There are through-lines where we hear the flatline tone, sometimes from both sides. Occasionally, voices can be heard on the other side as well. The audience hears people trying to revive a character from the other side. Then some of the voices from the supernatural world will follow the characters back to their everyday lives. Dolby Atmos allowed us to play up both sides. We used the Atmos in the flatlines and altered realities and then used a traditional surround mix in the natural world.

Esparza: The director wanted to create a dynamic soundtrack and so when the movie starts we are in the real world. We keep things relatively straightforward in the track so that when the characters enter the flatline we open up into the Atmos in the ceiling and move things around the theater to give a denotation of leaving that more natural world.

Winter: It really has to do with how the flatlines are depicted. We are a slave to the image to a certain extent, and the flatline experience is this montage of visually affected images and flashes, camera pans...

Esparza: It’s a spectacle. It became very interesting and stylized on the flashes and that allowed us to do so much more. And like Mandell had mentioned before, we have the sounds occurring within the afterlife/flatline world itself. Since this is revolving around the idea that this is possibly brain activity that’s making all of these things occur, we introduce the idea of having these synthetic, electrical pulses and things incorporated into the montage of sound as well. But then we are also hearing the people who are still in the real world attempting to revive the character that is flatlining. So those sounds are maybe playing up in the ceiling, or behind us or moving around. Then when we cut mid-sentence back to the real world the dialogue will pop back to the center channel, like in a traditional mix, as we are seeing the characters actually attempting to revive the character that is flatlining.

Courtney (Ellen Page)

Courtney (Ellen Page)To enhance that in Atmos, were you using multichannel reverbs?

Esparza: A combination of Exponential Audio’s reverbs allows you to use a multichannel reverb in the bed. So to the seven-channel reverb in the bed we could link an additional stereo reverb that follows the same settings. Those two channels are in the roof, and together it’s a nine-channel bed. When you hit that reverb, it plays through the seven channels and it also pushes up to the upper two channels as well.

Also, there was extensive use of Cargo Cult’s Slapper plug-in, which is a multichannel delay plug-in that lets you position the individual delay taps in a seven-channel field. I used that a lot on the sound effects, and the dialogue/music re-recording mixer David Giammarco used them on the vocal treatments in the flatline experience as well.

After the students have flatlined, they start to experience strange things in their everyday lives. How do you use sound to portray these altered reality events? Were there any guidelines to what these moments could or could not sound like?

Winter: It was driven by story more than anything. For example, the character Courtney (Ellen Page) is haunted by her sister, by the last words that her sister said. So she’s constantly hearing that as she is being haunted. The other characters have their motifs as well, like Sophia (Kiersey Clemons) with these laughing and giggling girls and Jamie (James Norton) is haunted by this baby cry. It was really story-based.

Esparza: It all plays into their individual experiences. The things that the characters are haunted by are things that occurred in their past. Those things, sonically, start out the haunting experiences when they come back.

“The flatlines were very subjective, montage-like moments that have a lot of transitional effects like swhooshes and hits. We introduce these synthetic, electrical pulses and things to denote the idea of the brain synapses firing."

Did you have a favorite moment of altered reality?

Winter: There are a couple for me. One I really like is the car driving sequence when Marlo (Nina Dobrev) is being attacked by the past that is haunting her while she is driving. So we see the flashes of her being attacked, and then it cuts back to her just driving in the car by herself. The person who’s putting the bag over her head isn’t really there. We contrast the sounds of the struggling during the attack with no sound when she’s not being attacked — except for a low rumble and a high-pitched tone to denote that this is all purely in her head.

Esparza: One of my favorite moments is when the character Jamie is in the boat and he is haunted by a crying baby. He attempts to try and find the baby because he hears the crying coming from inside the boat. He realizes it’s in this cabinet, so he moves towards it and opens it up. He then realizes that there is actually nothing there.

For the mix there, we found that it was more interesting to not localize the baby cry to the cabinet because the shots of Jamie looking around happen very fast. To have the baby cry pinpointed to the cabinet would actually be distracting because of the way the scene was edited. It was more effective to keep the baby cry near the center but pulled slightly off the screen so it doesn’t feel like it’s directly in front of us, but at the same time we didn’t necessarily pan the sound around with each look he has. Sometimes that works but a scene really has to be edited or shot a certain way to allow for that moment to happen. Otherwise, it just feels like it’s jumping from one speaker to the next. It was creepier just keeping the baby cry in one place.

Since the crying was coming from the cabinet it starts off muffled and low. As he approached the cabinet and pulls the pillows off the area, we slowly increased the sound, making it a little louder and less muffled as he opens it up. Each moment as he gets closer, we can feel the baby getting closer. That helped with the tension and made it feel creepy because the movements were all very slow. So as the cabinet is opened, the low-pass filter gradually comes off and the sound of the baby is demuffled. It helps with that creepy tension of what he is actually going to see when he opens the cabinet door and pulls the blanket off of the baby, which isn’t actually there.

Jamie (James Norton)

Jamie (James Norton)What console did you use to mix Flatliners?

Esparza: We mixed on the Avid S6. This was a totally native Atmos film. We started on the Beta version of Pro Tools 12.8.1, which had the native integration of Atmos in it. It had full nine-channel beds along with the new object bus switching architecture.

This was my first Atmos film so I couldn’t appreciate the technology as much as David Giammarco, who has done several Atmos mixes. He was there for the early stages of Atmos mixing, going through the growing pains of working through the technical aspects that had to be in place, like making sure both machines were online if you were going to punch into the objects. We didn’t need to worry about that stuff as much here because it was all native, inside the box.

Winter: It also made conforming easier. When we got picture changes we were able to send it back up to editorial — they also had Pro Tools 12.8.1 installed on their systems, so they could monitor everything in their rooms, including all of the objects. They could make the necessary changes and we would have all of the object automation right there.

What was your most challenging scene for sound?

Esparza: There is an elevator that the characters use to travel down into the basement level of the hospital where they are performing these experiments. It’s a part of the hospital that nobody uses, and there are no security cameras, so they would take this service elevator down to do their experiments. Niels wanted the sound of that elevator to be recognizable from the first time we hear it, so that later when we hear it in the film off-screen, the characters and the audience link it to that elevator and they know that someone is coming down.

We initially tried different metal squeaks and metal groans and rattles that were syncopated in an identifiable way. Every time the director heard it, he kept saying that we weren’t quite there yet.

We went through so many mechanical sounds for the elevator and eventually we landed on just putting in a buzzer, which really stood out. Realistically, an elevator like that wouldn’t have this kind of buzzer that we put in — almost like a warning buzzer that the doors were going to open. But in the context of the story, it actually worked quite well. So that was probably the area that went through the most trial and error before we landed on the right sound.

Did you get to do any field recordings for this film?

Esparza: We recorded a bunch of whispering and breathing and demonic voices. That was probably the most recording that was done specifically for the film. The schedule was challenging so we didn’t have a lot of time to do field recording. We did use a lot of recordings that we captured recently that happened to find a good home inside this film.

Winter: The funniest one was the fan sound for the morgue. We were working on a project last year and the fan in the bathroom at the facility where we were mixing had the strangest start-up sound. We would come in early in the morning before anyone else was there and the fan would just sputter on and sputter off. It was hilarious. David recorded it and we were so lucky to have that recording because it works so perfectly in this film.

Esparza: So when Marlo is in the morgue looking to recover some property of one of the characters, a haunting occurs and the first thing that happens is there is a giant power shutdown with the obligatory breaker-switch throw sound that is used as a big scare. Then to denote that all of the power gets cut out, we have that little fan that winds down at the end of that. As a fun little Atmos moment, we stuck that straight up onto the top of the ceiling, as though it is an AC unit that shutdown. That was fun, and it’s one of my favorite sounds in the movie.

Marlo (Nina Dobrev)

Marlo (Nina Dobrev)Can you tell me about the voices and the breathing? Were these sounds that you performed yourself?

Winter: I brought in some voice actors and recorded them during our loop group session. There was one guy in particular who was amazing with what he could do with his voice. He almost created his own reverb. It was really bizarre. It was great source material to put into the film.

Esparza: We did some treatments to that. Then some of our crew provided us with some of the breathing elements and some of the other demonic whispers that ended up in the film. The breathing elements were applied to the climax of the film when one of the characters is being sucked down a hallway that leads to this black vortex of darkness.

The director wanted to give it life so that we felt it was some sort of conscious entity. We used some breathing in the room that was performed by one of our editors. With that, we slowly started to create this suction vacuum sound as everything gets sucked toward the vortex. That sound starts off with some treated breathing that we recorded.

For processing, we did some pitch shifting and modulation effects with Soundtoys plug-ins like Crystallizer to help pitch it down and EchoBoy to create some space and size to it.

Any other audio tools that were helpful for creating the sound of the film?

Esparza: I want to mention Symbolic Sound's Kyma sound design environment. I used it extensively in the processing of wind and vocal elements for the flatline sequences, and for textural sweetening in the hail storm scene.

Is there anything you’d want other sound pros to know about your work on Flatliners?

Esparza: I would say to respect the work that your picture editor has done to the track. When you get a turn-over to a film, the picture editor has already done some sound work. The picture editor on Flatliners, Tom Elkins, is a fantastic editor and he’s great with sound too. He had a lot of great ideas and initial concepts crudely sketched out in the Avid. We were very mindful of all of the work that he had put into his track. We followed the shape of some of those concepts that he laid out in the flatline sequences and hauntings because he had put that work in and they got the rhythm of that working. Part of our job is not reinventing the wheel, but making the wheel bigger and better.

Some of it also had to do with the challenging schedule. Sometimes there isn’t time for extreme experimentation. You don’t have time to try and find the outer reaches of what can be done. Sometimes you have to stay within the framework that has been presented for you and a lot of times that comes from the picture editor. So I would say to always be mindful of the editor’s tracks. If they are expecting that particular shape to be followed then you have to design your sound around those ideas and concepts.

Another thing I want to mention is that it is possible to do a film about death without using a heartbeat as a major motif in the film. It’s a cliché because it is an effective primal sound that everybody can identify with. But because of that, it’s an overused motif. The heartbeat sound does make an appearance once or twice in the film but it’s not an essential sound that would be called back on as a central motif. We were able to free ourselves from that on this one and it was refreshing.