You asked, he answered: Get insight and inspiration from this community Q&A with Mark Mangini.

What would you ask two-time Oscar®-winning sound artist Mark Mangini?

With 46 years of experience in the audio post production industry, and 150 film sound credits including recent blockbuster movies like Dune, Mad Max: Fury Road and Blade Runner 2049, Mangini has a lot of knowledge to drop about film sound as an art form.

Since Mark is a Pro Sound Effects library partner, we asked our social media followers to send in their burning questions. Mark provided detailed and inspiring responses – from his experiences working on Dune to why sound artists should study improv comedy.

Read Mark's answers to your questions below, and be sure to follow us on social media to let us know who you want to interview next!

Mangini records sounds for "Dune" with Theo Green. Photo Credit: Peter Fisher, New York Times

What’s one skill you wish you could have developed sooner or known earlier in your career? (@_koaudio)

How to respect my inner drive and creative impulses, freeing me to be more of who I am rather than whom I wanted to become or imitate.

Were you influenced by the original Dune’s sound design? If so, what elements of it inspired you. And did you secretly pay homage to some of it in Dune 2021? (@svijayrathinam)

I wasn't influenced by the original Dune sound design in any way. I didn't really like the film, either. While I was and always have been a huge fan of Alan Splet and his work over the years, our Dune was to be an original film in every way: visually, dramatically and sonically. And we stayed true to that philosophy. There is/are no secret homage to the first film sonically. If anything there were a few sonic tropes we set out to avoid that included shields that "hum" and worms that roar. My partner Theo Green and I wanted something that felt organic and real, avoiding electronic sources that were more popular for science fiction in the 80s.

Newer technology such as Dolby Atmos has raised the ceiling for sound editors and re-recording mixers, what do you think is the next frontier? (@mosma_midoceanschool)

Redefining ourselves as artists and not technicians. Arriving at a time when filmmakers include us regularly in script development, pre-production and shoot, and acknowledging the storytelling power of sound with credits commensurate with other more established disciplines like Cinematography, Writing and Production Design.

Do you need anyone to make the teas and coffees? (@jaywhittaker_bhpsound)

Thanks Jay, but no, I'm pretty good at it myself. What I do need is more time, budget and respect... the stuff all of us need.

Do you have any special plugins to limit, compress or enhance the mix? (@cmedinausma)

Tools don't enhance mixes, ideas do. Don't peg your value or utility on the plugins you use. The best way to enhance the mix is to figure out how sound enhances the story...then go do that.

How do you control dynamic range during scenes? Is there a loudness limit you never get or does it depend on the mood and narrative point of the scene? Thank you Mark, really admire you! (@willyvila_)

We control dynamic range through constant review and refinement. It's vital to get a mix under your belt and then take it out of the mix room and screen it and see it as a movie to get a sense of its overall dynamics. This is vital. I prefer to final mix quickly, getting a sketch of ideas into a first pass and then watching it as a film. Then iterate as necessary till you get where you want. You can't really get a good sense of dynamics when you're mired in a scene or reel for hours or days on end. Make some smart decisions quickly and move on to the next scene. Then watch your film and take notes and come back to it. So, for example, if you have two weeks to final mix, get a version of it done in four days, watch it and come back for refinements. That down time between will give you so much more perspective about the dynamics of the film as a whole than sweating them in the trenches while over-analyzing every sound and cue.

"If you have two weeks to final mix, get a version of it done in four days, watch it and come back for refinements. That down time between will give you so much more perspective about the dynamics of the film as a whole than sweating them in the trenches while over-analyzing every sound & cue."

Mangini with David White accepting the Oscar® for Best Sound for “Mad Max: Fury Road" in 2016.

Photo Credit: Aaron Poole / EPA / ©A.M.P.A.S.®

What traits do you think set up new sound designers for success? (@noahghola)

Improv Comedy, Acting, Songwriting/playing a musical instrument, Public Speaking, and Psychoanalysis. Improv Comedy because you will be required to think on your feet and respond quickly and instinctually. Acting because you can’t know what sounds to use until you know why to use them. The WHY lives in the plot and the characters motivations. Songwriting because Sound Design IS composition. You just get to use more than 12 notes and your work is more than diegetic, it spans entire projects. Public Speaking because you need to pitch your ideas with fervor and conviction, like you want to convince an audience of more than one, yourself. Psychoanalysis because you need to know how to read your collaborators, sense their unspoken moods and needs, and cater to them in variegated ways. These are all muscles that need to be exercised and made stronger through repetition. Make them second nature.

How can I incorporate sound design in a script for a documentary that doesn't specify sound, or is not based in sound? What can I base a proposal on if the documentary doesn't have a script finished? (@genesisintilde)

Ask yourself these questions: How might sound tell this part of the story more efficiently than words or exposition? How vital is sound to this scene that using a shotgun mic or lavalier mic might not capture its essence? How would the non-literal (non-diegetic) use of sound tell my story and what can I be recording that achieves that while I’m filming?

Is mentorship a common practice in sound design? And if so, how do those relationships come about? (@noahghola)

I am not an authority on what the global community is doing regarding mentorships. Nonetheless, I know many sound designers use assistants to help them manage their studios, assist in setups and data management and many other responsibilities that might take time away from a designer doing the creative work. In this process, mentees and assistants garner first hand knowledge of techniques and skills and are often given design tasks to take on that the designer may not have bandwidth for. One might also see the relationships between supervising sound editors and the sound editors they work with as mentorship. My career saw a very traditional growth path from apprentice to assistant to sound editor to supervising sound editor. Along the way those who were my superiors always imparted knowledge so that I might grow and advance.

I have worked with so many incredibly talented sound editors who have gone on to brilliant careers as supervising sound editors. During that process, I have always tried to impart my creative knowledge as we collaborated on films together so that they had foundational knowledge that was not film specific that they could take on to their own careers as supervisors when they were ready to take the leap. Do not get hung up on the term sound designer and supervising sound editor. They are, effectively, the same person. They are entrusted by the filmmaker with executing their creative vision. These skills encompass so many disciplines that are learned through experience vs in a classroom and serve any sound artist. While watching what equipment or techniques a sound designer uses might be useful in an early mentorship, understanding WHY they used a technique or piece of equipment is so much more valuable.

These relationships come about in hundreds of different ways. But they all start with determination and focus. I interview a lot of film school graduates every year. I can tell you that the ones that succeed have already chosen sound as their vocation and are living and breathing it every day. That impresses me. Most interviews that I do come as a result of a recommendation from a teacher or peer in the sound community. So networking, having a demo reel, and some passion are a good first step. These relationships come about because you create them. Create them by always being friendly, available, honest and reliable. Simple human traits often impress more than technical skills.

"While watching what equipment or techniques a sound designer uses might be useful in an early mentorship, understanding WHY they used a technique or piece of equipment is so much more valuable."

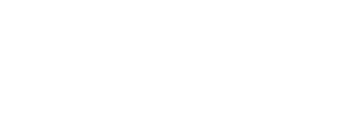

Mangini sitting at a moviola editing machine at his first gig at Hanna Barbera Studios in Hollywood, 1977.

What’s your go-to rig when you are on holiday? (@havasia)

Depends on the holiday! I try to turn off work when I vacation so I almost never bring quality gear with me. However, one never knows if something good is going to come of it so I usually bring a handheld recorder with me, just in case. I have a Zoom H1 that I carry around a lot. It’s just good enough for the odd sound(s) that I didn’t anticipate. That being said, I had a holiday in Qatar recently and I knew I wanted to record sand dunes (and my wife said it was ok to take an afternoon for work) so I brought my MixPre-6 and some mics in a separate luggage. If I’m going somewhere that I know will have an exotic sound that I wouldn’t otherwise be able to record, I’ll bring a small rig with an Ambisonic mic and a couple of CCM 41s. Oh yeah, I always bring my Sennheiser AMBEO Smart headphones. These allow me to record anytime (and very discreetly) in binaural. Good mics that record to the iPhone and no one knows I’m recording.

How do you like your ambience to create the feel of the space – like multiple stereo or a surround recording of a similar space? (@wari_wari_tiwari)

My basic technique is to build on top of a really strong surround recording with monaural spot FX to sweeten and give life. I generally eschew using multiple stereo recordings for a number of reasons. The first is that they do a very poor job of creating a believable correlated sound field. Second, they generate too much “build-up” in the detail area I want to control. If I wanted to create a nice forest birds environment, stacking two or three stereo recordings multiplies the number of birds and makes the ambience sound too busy. Same with crickets, traffic etc. If you start with an Ambisonic or multi-mic surround-sound recording, you already have a very believable bed on which you can apply very clean and detailed specifics, adding tasteful reverb (immersive) and delays (immersive) to place them in the same environment. One of the fun techniques is to play with immersion when moving in and out of interior and exterior spaces. Intuitively, we might make exterior spaces sound more immersive than interior spaces but flipping that logic can do some interesting things as well. Use immersion as a creative tool to maximize audience focus. Before considering the content, consider how you will expand and contract immersion to narrow or enlarge the audience's focus on a thing or event.

Is there any particular sound effect you created that you don't like and that you would re-do if you had the chance? (@marek.audio)

I’m sure there is, but I can’t think of it right now. My most painful memories are not of specific sounds I made but of my failures of imagination or my inability to convince a filmmaker of a valuable sonic point of view. More specifically, in my early career, I was afraid to speak up. I often had great ideas that never made it to the screen simply because I was afraid to take the risk of proffering the idea and its’ possible rejection. These feelings are exacerbated by moments when someone else in the room had that same good idea, offered it, and was lauded for it. I still hear those missed moments for me in films. Battle wounds.

Is there any movie from the past that you wish you were given an opportunity to work on? (@lukas.lulei)

Not really. There are classic films like The War of the Worlds (1953) and Forbidden Planet that I stand in awe of their sonic accomplishments and wonder if I could ever do something as good. In fact, this is the case most of time when I go to the movies even now. When I love a movie, I come away thinking “How did they do that… I could never do something as good.”

What is your process of choosing sounds from a library after spotting a new scene? Do you (or an assistant) skip through libraries and collect sounds that might fit in folders before editing the scene, or do you directly drag sound effects into the DAW during the editing process? (@pink_panda_sounds)

Phew… that’s a complicated one. I’ll try and simplify. My process, after spotting a new scene is to make lists of the following: What do I need to record, what do I need to design, what do I have library for, and what can I purchase that I can’t record or have in my library. This sets in motion a series of events that dictates everything I do. What I need to record is heavily influenced by what I need to design. Maybe I have an idea for a designed sound that requires a fresh element I don’t have library on. What I might purchase is heavily influenced by what I have in my library already and it’s age or quality. All these lists interact. I never delegate any of this work to an assistant. Once the lists are created, I will build “kits” for editors whom I work with (as well as myself) by browsing my library and making folders full of recommendations from it to impart my sonic sensibility on those parts of the movie. These kits often populate the raw (unedited) edit/mix template region lists that I give to the editor I work with. This allows them to start the process of editing with some basic ideas of where I want them to go. That being said, I rely on the editors I work with to pull/drag sound effects into their DAW as they edit, based on need and their creative instincts. This is the most fun part of the job, seeing/hearing how others feel about a scene as they contribute in ways I hadn’t thought of. I edit a great deal on my films too. And I am constantly in my library as new ideas crop up. Editing is not a mechanical endeavor. It is that wholly creative endeavor of bringing a sound-track to life from nothingness…to somethingness. For this process to really reach its highest potential, it cannot or should not be prescribed by lists.

"Editing is not a mechanical endeavor. It is that wholly creative endeavor of bringing a sound-track to life from nothingness…to somethingness."

Mangini recording gun sounds

In Dune and Blade Runner 2049, there seemed to be a great collaboration of sound design and score. Is this usually the case, or does it depend on the director? And are your design decisions ever influenced by the score or vice versa? (@ChrisVoltsis)

There was great collaboration between music and sound on those films. It is not as common as it should be but Denis Villeneuve is a very progressive director and he aided and supported and endorsed all the collaboration we had with Ben and Hans. This success will depend heavily on the director for a number of reasons. Denis is very focused on what he wants, he is usually quite clear and reliable on where he wants sound to lead and music to lead and where the crossovers are. As such we begin building these very early in the process, earlier than most, and have already worked out many of the collisions that occur at mixes when they haven’t been talked about or coordinated. It also requires a director who can speak meaningfully to the composer about this. Some composers are NOT open to this collaboration and see the music as alone and separate, inviolable. It takes a smart director to navigate these treacherous waters.

Needless to say, design is ALWAYS influenced by score. Not necessarily, though, score by design. It is startling to me to go to modern scoring sessions and hear new cues being recorded without playing back in the control room to the existing sound and dialog tracks. Is it arrogance or lack of awareness or naivete that can see the music living in a bubble like this? Perplexing.

In your blog you've mentioned that you're confident enough in your post processing of raw recordings that you delete them after editing and adding them to the library. Can you share some of your Do's & Don'ts of mastering sound effects? (@currywhiskers_)

- Don’t make hundreds of individual masters from a series of similar sounds

- Do monitor on the best speakers you have

- Don’t be afraid to high pass unusable low-frequency information if it is not germane to the sound

- Do cut out as much dead air at the head of a cue and in between events in a cue

- Do cut out slates and other verbiage that pollute the sound

- Do make file names succinct such that they are legible in a DAW

- Don’t put Designer, Microphone, Library name or other non-essential data in a filename

- Do encode Ambisonic A format to B Format before mastering

- Do not master Ambisonic A format in your library

What’s your favorite genre to design sound for? (@itshafeed)

Comedy. Because funny sound doesn’t require funny sounds. The joy is finding real sounds that make a scene funny because they comment on the narrative (or play against it). That’s really hard to do.

How much time does it take to make the sounds (recording, editing, designing, etc) for a movie like Dune? (@juancsound)

There is no one answer. For Dune, we originally had about 9 months for design through final mix. That was extended by the pandemic (as was the release date) that gave us several additional months. Blade Runner 2049 had a similar schedule. From my perspective in Los Angeles, this is non-standard and generous by almost any standard for post-production. But Denis Villeneuve is not an ordinary director. FWIW, Theo and I get about a month, once the film returns from location, to play around with no one bothering us before we have to start actually delivering usable sound design. This is our favorite time because we are allowed to experiment and take risks and pursue hunches. That’s hard to do when on a schedule and delivery time-line. When I’m on a typical studio movie, I usually get around 12 weeks for this same process. I’ve also done documentaries and low budget films where my prep was four weeks, sometimes less. I like the pressure. Sometimes these deadlines instigate ideas that wouldn’t have come without it.

"I like the pressure. Sometimes these deadlines instigate ideas that wouldn’t have come without it."

Mangini recording vehicle sounds with Eric Potter

When working on big blockbuster feature films and TV shows, how do you handle mental & physical health? I feel it is very easy to just work on a project of that size & only focus on that until finished with no time for one's own self. (@fendergibson22a)

Whether big blockbuster or indie doc, my work habits are the same. Which is to say, fraught with anxiety. One thing I know for sure, which is an outgrowth of my work as a musician: when in the "moment", never interrupt it. It might not come back. That is to say, never interrupt creative output, go with it till it's done...even if it means violating the prescribed hours you are meant to keep. If you were writing a song and were really "in the zone" would you quit at 7pm and not finish? Of course not. So too with Sound Design. Finish it and then take a break the next day to compensate for the time. I'm hyper vigilant about my fairness to my employers and collaborators. If I worked 48 hours straight to finish something important to them and me, I'd take 48 hours off to recover and we'd be square with that. My union doesn't want to hear this but I find that this is a more humane way to live, as long as its driven by my desire to do something great and worthy and be fair to the budget at the same time. I'll always put in the hours expected in a week I'm being paid for, but not necessarily in prescribed times and chunks. I think this is, ultimately, the most humane way to work. Aspire to greatness and do what it takes to achieve it, then figure out a way to balance that against everyone’s expectations. It's so much more organic. Our lives and our brains and our creativity don't follow time clocks. You shouldn't either, when creativity and greatness are expected. Just balance it out so that everyone wins, in the end.

Create beyond your imagination with The Odyssey Collection

We teamed up with Mark Mangini and his partner-in-sound, Richard L. Anderson, to create The Odyssey Collection – a series of world-class sound libraries developed from their private collection. Boost quality and creativity with masterful, big-budget, and rare recordings captured while creating the sound for over 250 Hollywood feature films and TV shows.

Want even more sonic wisdom from Mark Mangini?

Check out our Sound Effects Master Class with Mark Mangini created in collaboration with SoundWorks Collection. Discover how Mangini approaches new projects and various styles of sound design using his sound effects library.