Shape your sound effects to fit perfectly in a mix using tools and techniques like gain reduction, reverb, EQ, and panning.

Good sound design begins with finding the right sound effect for the job, but the best sound effect can be rendered useless if it is mixed badly. Here are some key aspects to focus on to ensure that your sound effects sit correctly in the mix.

Loudness

Determining how loud a sound effect should be in a mix is a great place to start. Let’s look at a few examples to understand how this makes a difference. If your scene involves a character taking off a piece of jewelry and placing it on their nightstand, the sound effect to accompany this will need to stay in the background and match the perspective of the visual. Using a close-up recording with a lot of detail that is very loud would feel out of place in the mix of such a scene. Another example is that of a cozy winter setting with a warm fire crackling in the fireplace. You want the fire to add to the atmosphere of the scene, but in the background. Lastly, let’s say you have a situation where two characters are talking to each other outdoors and it’s raining heavily. While the perception of rain is important to underscore the mood of the interaction, you still want to be able to hear them clearly and understand what they’re saying.

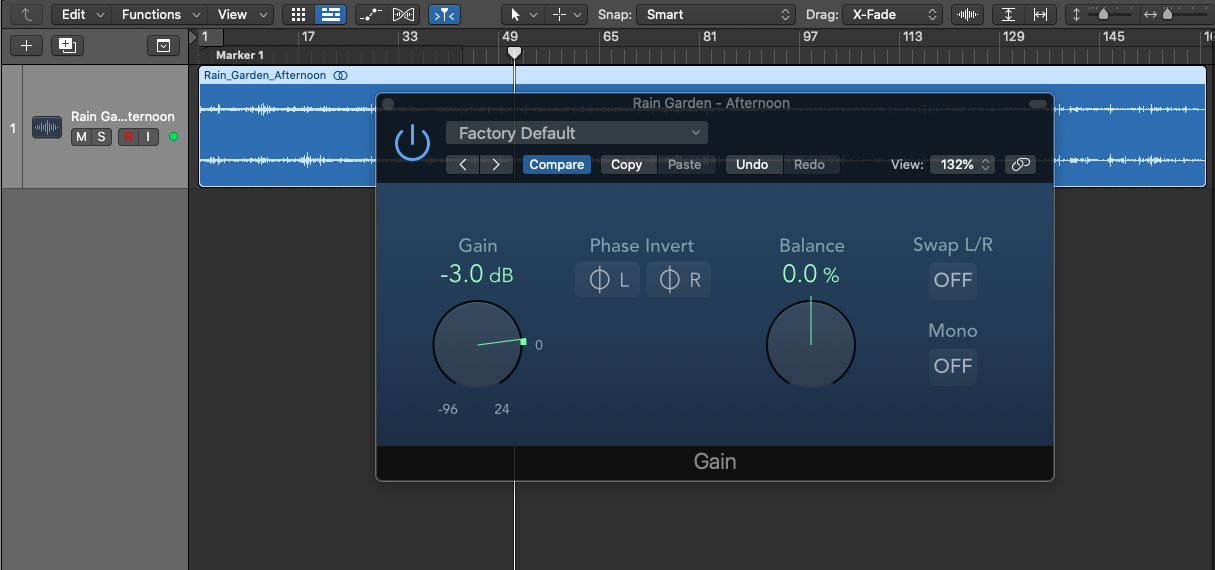

In any of these cases, before reaching for other tools, it’s worthwhile to see if some basic adjustment to the clip gain can achieve the desired effect. Turn down the sound of the jewelry on the nightstand until it’s an accent to the scene and not the focus; set the levels on the fire sound effect to a place where it hints at warmth and coziness; decrease the gain on the rain sound effect so that it doesn’t interfere with the intelligibility of the dialogue.

Ultimately, the creative direction of the scene will determine the choices you make – are you going for realism, or are you going for a deliberately exaggerated use of sound effects to emphasize a plot point or emotion? For example, if a character has just learned something that turns their entire world upside down and the glass they were holding slips from their hand and shatters on the tile floor, you may want the focus to be on the sound of glass shattering as a metaphor for their life falling apart. In this case, the sound may need to be close-up, detailed, and loud in the foreground of the mix.

"Ultimately, the creative direction of the scene will determine the choices you make."

Adjusting gain and balance can help sound effects fit more appropriately.

Distance

The next aspect to consider is distance – that is, how far away is the source of the sound? Do you want that revving car engine to sound like it’s just outside the window or do you need it to appear like it’s further down the street? Is the person shouting in the same room as your character or are they a few stories up, in the same building? In these cases, a simple volume adjustment won’t sell the effect. While it is true that as a sound becomes more distant, it becomes softer – that isn’t all that happens.

We perceive sounds that are further away as having less high-frequency energy and less detail than sounds that are closer. Distant sounds–depending on the environment–also have more reverb. To illustrate, have you noticed that a police siren becomes louder and sounds fuller as it gets closer? Or that the crunch of gravel under footsteps makes them appear closer than just the muted sound of footsteps on a street?

So how can you adjust the perspective of your sound effect to make it sit better in the mix? This is a multi-step process. The first step is choosing the right sound effect by examining the metadata of the recording itself. A good sound effects library will detail the perspective of the recording – for example, in our Water Flow Library we have ‘Small Rolling Waves, Medium Distance' and ‘Small Waves, Passing Close’. If you find the sound effect with the correct distance at this stage, you’re in luck and most of the work is already done. If not, you can use tools to achieve the desired effect in your mix. Use EQ to attenuate the highs, thus making the sound seem more distant. To adjust the sense of space in a mix, add reverb, which will push the sound further back in the mix. Then, adjust for volume. Turning down the dry signal in proportion to the reverb can alter the perception of distance. Also important to examine is if you’re using a static sound, or one that’s moving. Keeping these variables in mind, adjust your settings to help the sound effects seem more perspective-accurate.

Bonus tip: when there is movement involved, include a Doppler effect in your effects chain. Like we discussed earlier, as sounds move closer and farther away from us, there are changes in the perception of frequency; this plug-in can make the sound effect seem more realistic.

"The first step is choosing the right sound effect by examining the metadata of the recording itself. A good sound effects library will detail the perspective of the recording."

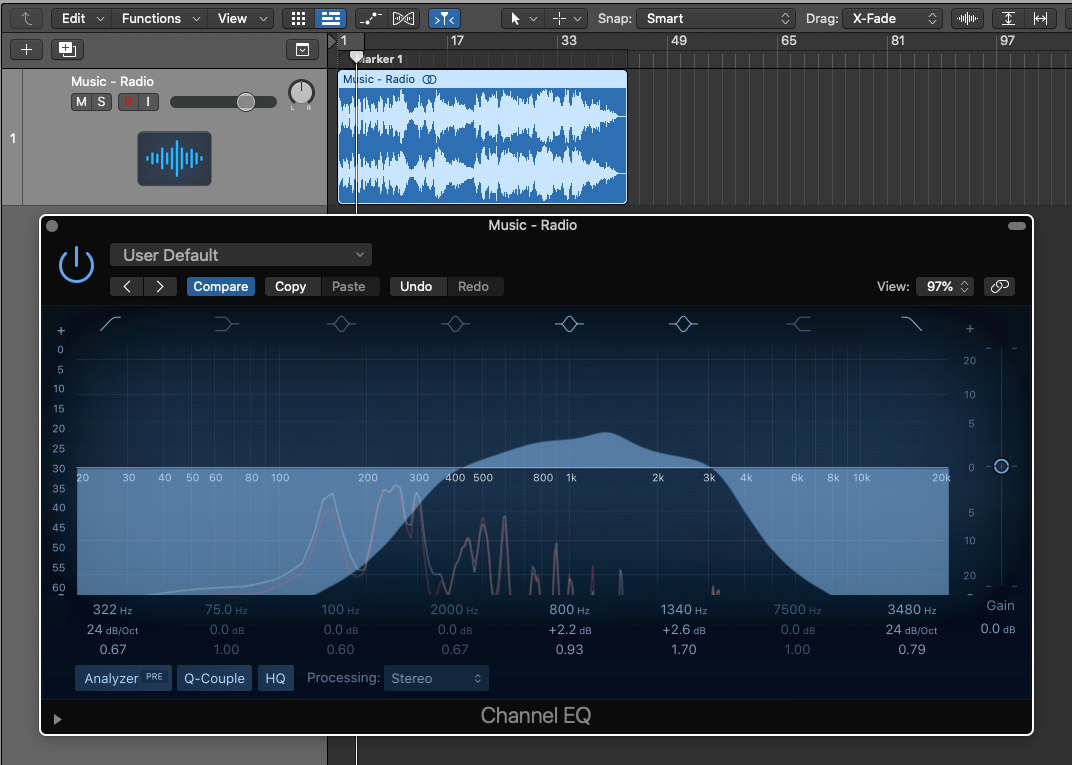

Adjusting the frequency of various sound effects is crucial

Frequency

Altering the timbre of a sound changes our impression of what it is. For example, rain sounds very different when you are indoors than it does when you step outside; an explosion with debris detail feels closer than a muffled blast without detail. When selecting a sound effect for your mix, keep in mind the context in which the effect will be used.

We have already discussed using EQ to sculpt the frequencies of your sound effect. Let’s look at some other ways in which it can help your effects sit better in a mix. As an example: say you have the perfect piece of music for the scene but it has to sound like the music is playing off a radio in the background. In this case, simply layering the music into the mix is not going to give the impression you need. This is when you turn to your tools. Start with EQ: boost the mids, cut the highs and the lows. Then, decrease the gain on the clip. Finally, if the scene is an indoor setting, add a room impulse reverb to properly sell the effect. Now you have helped the listener feel like they are hearing music playing off a radio.

Location

We’ve already covered one aspect of sound localization – the distance of the sound effect. Let’s now think about where in the stereo field a sound comes from. The pan knob moves sounds to the left or right of the stereo field. Some sound effects already have panning built into their very nature, such as flybys, drive-bys, and whooshes, to name a few. For other sound effects, you might want to use panning to indicate placement in the stereo image – for example, a telephone ringing off-screen, a voice at the door on the left of the room, or footsteps going from left to right.

Final Takeaways

With judicious use of gain reduction, EQ, reverb, and panning, you can shape sound effects and create spacious and clear mixes where each sound truly fits into its own place and benefits the entire project.

Sonal D'Silva is a freelance sound editor and designer with a decade of experience working with music, dialogue and sound design elements for video projects. She also composes and produces music and is an alumnus of the Berlinale Talent program and the Red Bull Music Academy.