Renowned field recordist Lang Elliott shares his story and demonstrates how to create immersive nature soundscapes.

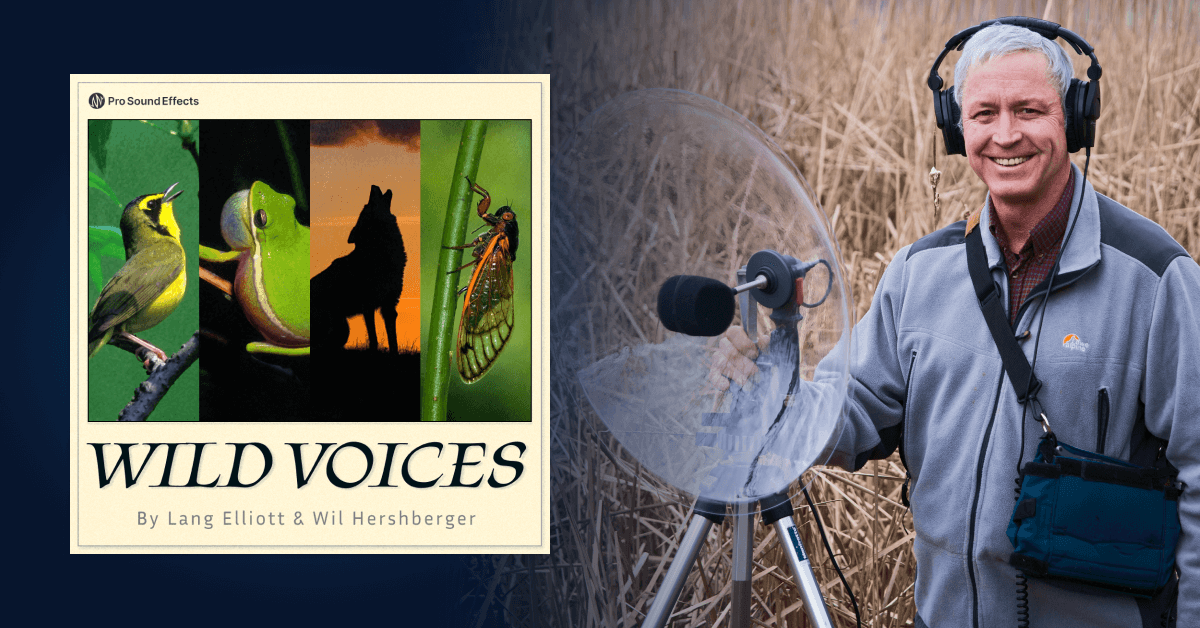

Lang Elliott is many things: nature lover, acoustic ecologist, hearing loss survivor, immersive soundscape creator; and now, the latest sound artist to join the Pro Sound Effects family. Elliott’s first PSE sound effects library, Wild Voices, brings together more than 1,500 recordings from throughout his career, offering sound designers an immense collection of isolated animal sound effects that are perfect for spatial audio workflows.

To celebrate the release of Wild Voices, we invited Elliott to share his story, discuss what makes Wild Voices so unique and useful, and explore some of the included sounds with immersive binaural examples.

How did you first become fascinated by nature and sound?

Lang Elliott: I took a herpetology course back when I was an undergrad, and the guy who taught the course was a real field biologist, so we went on some field trips to southern Missouri. There were all these frogs and toads that were new to me and the sounds were amazing, so for my term paper, I wrote about the calls of frogs and toads. I obtained a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder and a parabolic reflector called the Dan Gibson Wildlife Sound Parabola. I would go out and mostly record frogs and toads as part of that course, and that really got me into both listening and recording.

After that, I went off to the University of Maryland and studied animal behavior and ecology. Then I moved up to the Adirondack Mountains and became sort of a freelance naturalist teaching courses at a local community college. Through that, I met this guy named Ted Mack. He was a librarian, but he was an expert on birds. He knew every bird sound there was up there, and even farther out into the United States. I was fascinated by all the birds he was hearing and pointing out, so I started getting more and more interested in that.

What are some of the challenges of recording in the field?

There's a whole sub-story here. I actually have high-frequency hearing loss from a firecracker accident and a period of target shooting without ear protection when I was younger, so I had shied away from birds because there were a lot that I couldn't hear. I thought I couldn't really work with sound, but ultimately I got really fascinated and I actually partnered with some people to develop devices that would let me hear the birds again.

I went on a long recording trip with Ted, and at the end of the trip I actually had better recordings than he was able to get, even though he had superb ears. With my devices, I was able to go out and do it. I just ended up having a knack for birds, and I got really fascinated and interested in their local repertoires.

Throughout my whole adult life and my adventure with sound, I've had this impediment of not being able to hear the high pitches, so I can only do my work effectively in the field with the help of these devices that I developed that lets me hear birds that I wouldn't otherwise hear. And of course, I record what they really do, not what I'm hearing, which is actually a pitch-lowered version.

"I just ended up having a knack for birds, and I got really fascinated and interested in their local repertoires."

Lang Elliott and Ted Mack on their first recording trip in 1988.

What makes Wild Voices different from other animal sound effects libraries?

Several things. One is that there are really no comprehensive (North American) collections out there in the sound effects world. Wild Voices has over 1,500 recordings and more than 500 species of birds, frogs, insects, some mammals, and a handful of reptiles. That isn't available out there as far as sound effects libraries that I know about; they're usually smaller productions.

But what really sets it apart is that these recordings have no backgrounds. When a sound designer wants to sweeten a production with a bird or a frog or something, background sounds become annoying when you try to position that recording – especially when you're doing spatial audio. This library addresses that because it's giving you objects: a bird and nothing else. You can put that bird wherever you want to. You can spatialize it; you can reverberate it across the environment.

When we listen to a sound in the real world, it's the reverberation that marries it to the environment and gives this sense of realness. The average listener doesn't think about this; you just hear a loon on a lake and you hear all those echoes. But if you're going to take a recording of a loon and put it in a production, if it has all that echo in the recording, it's stuck to the sound object. It's stuck to the loon, but the reverberation doesn't happen where the loon is; it happens elsewhere.

Wild Voices gives you a totally clean and clear rendition with low reverberation, and the recordings are all monaural so you can put them out into space and then tie them to the environment and breathe life back into the recording. These objects are ready-made for this new wave of object-based audio; you can use software to spatialize the sound and reverberation to spread it out across the environment.

"When we listen to a sound in the real world, it's the reverberation that marries it to the environment and gives this sense of realness."

Lang Elliott with a soundscape mic.

You’ve provided a few of your favorite sound effects from the library, along with some examples of how to implement them in a spatialized soundscape. What can you tell us about these sounds?

*Note: the spatialization examples below are rendered in binaural format. To hear the full effect, listen with high-quality headphones or in-ear monitors.

American Bittern

This is a member of the heron group called the American Bittern. It's a smallish or medium-sized heron, maybe up to two feet tall. It's brown, rather nondescript, and lives out in the cattails in big marshes. The male produces this amazing sound. It's very resonant and you can hear it a mile away, if not farther. They give it different names; one common name is the “pumperlunk.” In the literature, they would call it the “stake driver” because the echo was reminiscent of people on railroads banging a stake.

For the binaural example, I just took a marshy ambience in binaural and then spatialized the American Bittern sound object using dearVR PRO. But the magic is in the reverb – when you just spatialize a sound in a binaural field, it doesn't sound real because it's missing the reverberation in the environment, which is what makes it believable. So I went in and used the reverbs that are available in dearVR PRO. Some of their standard ones work really well to create a believable outdoor kind of field.

Cane Toad

This species is common in Central America and South America, but it ranges into the United States in two places: in extreme south Florida and in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. They call from these canals down in south Florida, but there's always a highway right next to them, so I never was able to isolate one. But then I went down to Texas in 2005, right after Hurricane Emily went through, to record frogs that start calling after hurricanes. I found them in a flooded ditch next to a dirt road where there was hardly any traffic, except the Border Patrol that came and gave me a little trouble at one point.

A lot of the time there were two of them calling, and there were these Mexican tree frogs singing in the background. I couldn't extract a sound object that was usable because of these other frogs, but then there was one instance where those Mexican tree frogs stopped and this one toad trilled and the other one didn't overlap it. I got my best recording out of that. I was able to clean it up and spatialize it into a typical ambiance from that part of the world, but it's one of those sounds you could throw into most anything.

White-Tailed Deer

Deer do make some sounds during breeding, but the thing you're more likely to hear is – if you're out in the dark or you're camping in your tent and a deer comes close – they'll smell you. If they see or hear or smell you, they will do this huffy kind of a thing, and it's quite startling. It’s called a snort, and often they stomp their feet right at the same time. Then, if they get uneasy, they’ll often bound away snorting.

I got that recording at a favorite recording spot in Land Between the Lakes, Kentucky, by putting a mic out overnight. It was next to a little stream that wasn't making any sound, but I saw a trail and I thought, “Deer or something's going to be walking down that trail.” And sure enough, one came along and snorted five or six times and then got upset and bounded away. Fortunately, there was virtually nothing else happening sound-wise, so I was able to clean it up and it spatialized beautifully. In the example, I have him snort starting on the far left, and then he gets upset and runs straight in front of you and off the distance.

Snowy Tree Cricket

This is a member of the tree cricket family, which doesn't look anything like your normal black cricket. They're actually pale green in color and sort of translucent. If you saw one during the day, you wouldn't even know it’s a cricket. When they sing, they stick their wings straight up and rub them to make the sound. It's quite a posture, but hardly anyone's ever seen it. But the reason I love it is that it’s one of the lower-pitched crickets, so I can actually hear it without a hearing device. It's a very musical, very pleasing sound, and it pulsates. They often synchronize, so you get a group of them all going in sync.

In the example I provided, I put it far back just to provide a subtle rhythm to the recording that otherwise didn't have an element of rhythm. It’s just one example of how you might use a cricket sound to add a certain flavor to a recording. And there's not only the snowy tree cricket; there are a number that have that pulsation, but there are also crickets that just trill continually, and a bunch of insects that do other weird stuff like harsh, non-musical sounds. I tried to provide a variety, hoping that people will go in and explore them.

American Alligator

I made both of these recordings in Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. The hissing one was actually quite a ways back. I was walking on one of the boardwalks there, and there was about a seven-footer off to the side, and I poked it with the end of my tripod. I probably wasn't supposed to do that, but I didn't feel it was dangerous for me – seven feet is not a big alligator – and that's how he responded. He hissed at me, so I backed off, and then he did this sudden outburst and splash.

The mating bellow mainly happens in spring and early summer, and it’s an amazing sound. Such a low pitch, like a lion roaring. I was out there in the wilds in Okefenokee, and I canoed out to this floating platform, and there was a resident alligator there. I set a soundscape mic up as near as I could to where I thought he was, and come dawn, he did his thing and I got that recording very close.

"Wild Voices gives you a totally clean and clear rendition with low reverberation, and the recordings are all monaural so you can put them out into space and then tie them to the environment and breathe life back into the recording."

How can sound designers get the most out of this library?

I consider Wild Voices to be this huge palette of sound possibilities that the vast majority people are not familiar with. So you can go in and say, “I love the sound of the wood thrush, but what about the other thrushes? The hermit thrush, the Swainson’s thrush, or the veery; what do they sound like?” You can go into the collection, go to the thrushes and check them all out. It’s really important with North American owls, too. You know about the hoots of a barred owl or great horned owl, but there's all these tooting owls and whistling owls and a wide variety of sounds that are just amazing.

I’m hoping people will discover sounds in this collection as opposed to just searching for something, because there's so many things no one’s going to search for if they don't know it exists. I consider it a learning collection – there's so much there that I hope people really explore it and discover all these new sound sweeteners and possibilities that they don’t know exist.

Dante Fumo is a Midwest-based sound designer, editor, and mixer specializing in independent film and Dolby Atmos mixing. In his free time, Dante composes electronic music and publishes Harmonic Content, a zine about sound.