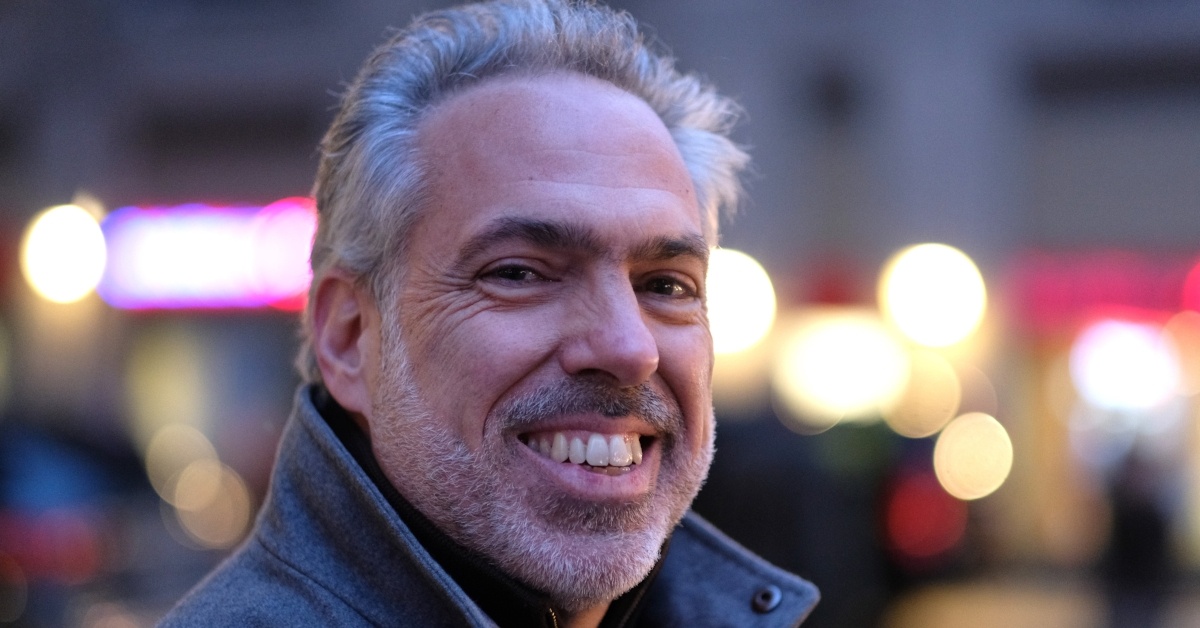

Learn about Jacob Ribicoff's long-time collaboration with filmmaker Ken Burns, and how he approached creating the Emmy-nominated sound for both The Vietnam War and Fahrenheit 451.

Since starting his audio post career in the early '90s, Jacob Ribicoff has had quite the successful journey – amassing an Emmy win, seven Emmy nominations, a C.A.S. nomination, one MPSE award and three MPSE nominations. He's known for his work on 2001's Jazz, 2003's School Of Rock, 2007's The War, and most recently both Fahrenheit 451 and The Vietnam War which earned him two Emmy nominations.

We had the opportunity to speak with Jacob about his start in the audio post production world, his decades-long collaboration with filmmaker Ken Burns, his go-to audio tools, impressing Roger Waters with sound design and more.

Could you describe how you began working with Ken Burns?

Jacob Ribicoff: With Ken Burns, it starts all the way back at The Civil War and before I ever got into the business of doing what I do as sound designer, sound editor, sound effects editor, mixer, and all that. I was just a regular civilian and tuned into The Civil War series as it aired for the first time. The thing that caught my ear and my imagination immediately watching that on television was these amazing civil war photographs. Let's just say you see a photograph of a battlefield after a battle with the bodies strewn across the field. And suddenly you're hearing a bird or something, and it's morning. It was so evocative to me through a few well-placed sounds how it intensified the degree to which I felt like I was there. Sitting in my living room watching this on TV, experiencing these photographs come to life, the evocation was very strong for me. So it was at that point I had become interested in sound.

Is that how you were first introduced to the process of audio post production?

Yes, I was aware that there were people out there called sound editors, but I had no idea that that was a career one might be able to have. It was very inspirational for me watching The Civil War and beginning to realize you could do amazing things with sounds as opposed to music; that you could use sounds in such a way that would really place a listener or viewer in a location, in a mood, or even emotionally get them to feel a certain way.

I was then curious as to who specifically was responsible for those sounds, and I learned it was an amazing sound editor named Ira Spiegel. Eventually once I had kind of broken into the business I was able to get a job as his assistant on a short film. It was like a dream come true for me, and that began an association with him where we worked on a few different projects together. Eventually in 1995 he said, "How would you like to put sound effects on The West?” which Ken Burns was producing at the time. It was really my first chance to cut sound effects on something, not a student film or low budget indie movie, but something that I knew was going to have viewers which was very exciting.

"Sound works on a subconscious emotional level in a way that image doesn't. To have that opportunity to tell stories with sound, I think that's probably the highest call that I could possibly imagine."

And you continued to regularly work on each of Ken's films from then on?

So after that was Thomas Jefferson around 1997, then around 1999 I learned that he was making his documentary about jazz. I'm a lifelong lover of jazz, it’s a music that's always been a big part of my life – I also used to play the saxophone. When I found that out I asked if I could be a music editor on that. Then from there was a whole string of music editing jobs with Ken on Forgivable, Blackness, The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, The War, National Parks, Prohibition, The Tenth Inning, The Roosevelts, Central Park 5... the list goes on.

Fast forward to Vietnam and they said, "We're doing this ten-part, twenty-hour series on Vietnam, and we want it to be very rich in sound design, not just literal sounds of what you see, but subjective sounds to really try and capture and get into the heads of, and the hearts, feelings, souls, if you will, of all of the veterans and the people speaking – Vietnamese folks and people on all sides of the war who were being interviewed and recalling and remembering.” And, of course, all of that is supported with incredible footage so I was able to be one of sound designers on this amazing series.

Ira, who I had started with, worked on Vietnam as one of the sound designers as well so Ken’s kept a group of people together through all these years. It’s been over twenty years from 1995 to now and we're like a family. It's great to reunite, to all get back together again and work on these jobs, and it's great seeing Ken again every time we all reconvene for a job.

What was the process like designing and editing the sounds for The Vietnam War?

On Vietnam we had a recording session about two or three days long where we were able to bring in a group of Vietnamese folks who varied in age, and we played scenes for them. Everything from very quiet scenes, whispering in a jungle setting to the fall of Saigon where it was just bedlam, and chaos, and hysteria. We did single voices, we did groups, and that stuff was like gold for us, because it was real. We were able to take that and mix it very low into the backgrounds. Using a little bit of foley for whenever we see somebody walking through a muddy rice patty, or a soldier handling their gun, with the combination of the voices worked out really well.

Our mixer, Dominic Tevella, who has been working with Ken also for a very long time, is a master. It's a matter of the level at which you can get away with mixing sounds at a low level, EQ-ing them in such a way that you're rolling off the high end, and maybe you're rolling off some low end, you're also narrowing that bandwidth frequency-wise. Then, all of a sudden it drops in there and it feels like it was always there, even though it's a piece of silent footage. The same goes for Foley, just playing it low so there's just enough there to kind of feel it and hear it on the peripheral of your hearing. It's always amazing how it works.

When you're working on these documentaries with older subject matter, what are your go-to sound libraries? Any tricks that you use to make things sound older and fit the context of the piece?

When I started working with Ken's company, Florentine Films, on that first job, The West, they introduced me to their library. Their library had so much, I can't even tell you where it all comes from. It all had this grainy, low-fi, narrow bandwidth character to it. We found very quickly you will never be using this stuff for any other job, but I was taught and I learned that this stuff was amazing when you put it on top of a piece of, either a photograph or archival footage that might have no sound or might be a newscaster talking over the images anyway. You could drop that stuff over those images, and then, boom, presto, it's like, "Wow. That's exactly right, and it feels great." It's amazing what it does. It's like just at the snap of a finger you're there, you're suddenly there.

In an industry where we're constantly judged on our work, how do you handle keeping up with the times and different trends that may be happening in the worlds of sound design or sound effects editing?

There's the aesthetic side of that and the technical side of that. Certainly there's the equipment we use, Pro Tools, and the plugins, and things like that. That's always changing, especially the plugins, especially a plugin like iZotope RX where they've come up with just these incredible ways of being able to clean sound, and even get the natural room echo out of a recording. I've used that on Vietnam on voices where maybe I had someone in a room yelling and screaming or something, but suddenly it calls for that voice to be outside. Because I didn't care so much if it was degraded a little bit, in fact if it was degraded a little bit it actually made it more effective, I could hit that voice with the De-Reverb and suddenly there it is, it's an exterior voice, there's this in and out quality, and it's great. It's actually working better. That would be one example of using something that's relatively new in terms of technology.

And then keeping up in a way aesthetically, for example while working on Vietnam with Ken and his team, we made this decision to go in a much more abstract direction at times. You have these backwards sounds, he uses almost like these stings in between scenes sometimes to signal that you're going into a flashback, you have someone recounting a story, something they experienced while on the battlefield, and suddenly we use one of those sounds to throw the viewer into this hyper-real or even this abstract version, or vision, of the story. At one point there's Jimi Hendrix's Are You Experienced? playing which has those wild backwards sound in it, and you go all the way back to that. There is definitely an aesthetic trend that you hear in popular music, in movies, of using all kinds of backwards recordings in the sound design, embedded in there. Then you hear it in a Jimi Hendrix tune that's used in Vietnam, but they use that backwards device even in the opening montage where some of the iconic footage is being played backwards as if to say, "If we could only have taken this back."

Certainly the use of sub and low-end information, the use of the surrounds, those are all things that I guess I've been doing this long enough to see where, say from the early '90's to now how they’ve evolved … On The War, which Ken and I worked on, we really made great use of the full 5.1 field by panning things all over the place. It's funny, for Vietnam we actually made the decision to scale back on that a little bit because when Ken would come in for playback, we wouldn't even play it back for him in 5.1, we would playback off of a television in stereo because he decided he wanted to make sure he was listening to something that was a lot more like what the average person was hearing out of their television as opposed to this theatrical experience, which very few people would actually be experiencing in their viewing.

iZotope RX

Do you have any stand-out scenes or moments from movies you've worked on over the past couple years that you're particularly proud of?

One thing that just comes to mind is the sound design I did on Roger Waters' The Wall concert documentary which we mixed in Atmos. Unfortunately it wasn't shown very much in Atmos, there was a one day release all over the world, and then the movie went to DVD. In between some of the songs you see footage of Roger going back to visit the grave sites of his father and his grandfather who both died in different wars. Grandfather in World War I, and his father in World War II. He goes back to visit those sites and it's very emotional. He's driving to get to those sites, and he's driving this beautiful 1960 Bentley, and he's on the Italian coast. There's a surreal device that's used where he's talking to someone who might be in the backseat, then he turns around and the person's suddenly not there. And then he turns back and it's maybe a friend of his, and then he turns back and it's his family, his kids are there.

There's another sequence that had to do with the war, and they had asked me to convey the spirits of those killed during the war in a sense of spirits floating over a battlefield or something like that. They had score planned for these sections in between. It came to one section where he's talking to a friend of his, and he's driving on the side of a coastal mountain. It was very emotional working in a somewhat abstract way, coming up with tones, and drones, and then some sub-explosions meant to evoke bombs exploding, or the feeling of remembering that. We got to this one section and he said, "You know, let's just use the sound design and not use the score." For me, and coming from Roger Waters with his rich history of using sound effects on the Pink Floyd recordings, that was a huge compliment. That was humbling and gratifying, it was a great moment.

What was it like working on Fahrenheit 451?

It was another amazing process where, in a short schedule with not a lot of lead time to research or what have you, I had a large crew. It was not just me doing everything, but I did spend a lot of time coming up with ideas and sharing them with other sound effects editors and sound designers and then everyone pulled together as a team. It was truly a great experience, everyone did such an amazing job on that. We really tried to personify some of the sounds, for example, the flame thrower sounds. It's the fire and the flames that in its evil way consumes the books that are being burned and, by extension, the soul and the culture that's conveyed and the humanity that's conveyed through those books and other forms of media.

[Director] Ramin Bahrani wanted the sound of the flame throwers to almost have a demonic quality. So I was able to go to recordings of cobras and other reptiles and get some breathing and things like that to layer into the flame thrower sounds. That was fun, and great that it worked so well. When the Micheal B. Jordan character is demonstrating them in front of this gymnasium full of kids and you first hear the flame throwers, each flame comes out and it's like (imitates sound). I can't do it over the phone, but you can hear it in the movie. We did the same with the fire engines too, to give them some bestial kind of quality.

“I think anyone who gets these kinds of nominations probably agrees that we work hard one project to the next - we don't skimp on any project, and you're giving them equal amount of your creative spirit, mind, time, energy and everything…It's great because you just take it as an acknowledgment of all the work that you've been doing and will continue to do anyway.”

What do your Emmy nominations for Fahrenheit 451 and The Vietnam War mean to you?

It's definitely gratifying to get those nominations… and it's a bit random. I think anyone who gets these kinds of nominations probably agrees that we work hard one project to the next - we don't skimp on any project, and you're giving them equal amount of your creative spirit, mind, time, energy and everything. And then all of a sudden, for whatever reason, maybe because they're popular across the board in terms of just the film itself, it's positioned so that it gets a nomination. It's great because you just take it as an acknowledgment of all the work that you've been doing and will continue to do anyway. You're gonna keep on doing the same job next year, the year after that, as you did ten years ago when you weren't gonna get anywhere near being nominated for anything.

Anything else you'd like to mention?

Where one would hope that a nomination helps you is to bring you to the attention of other filmmakers when it's time for someone to tell their story and they want to create a unique soundscape. I would hope that they would know who I am and give me that opportunity to try and do that along with them because that's what it's about. In the end, it's about storytelling and bringing the story through the whole language of movie making. It's bringing the story as deeply to the viewer as possible. Sound works on a subconscious emotional level in a way that image doesn't. To have that opportunity to tell stories with sound, I think that's probably the highest call that I could possibly imagine.

Amen to that!