Discover multidisciplinary sound artist and musician Chris Watson’s unique approach to recording and curating sound.

The latest PSE Sound Artist, Chris Watson, is a lifelong lover of sound. From his childhood recording experiments to his groundbreaking work with the electronic group Cabaret Voltaire and his award-winning contributions to BBC programs like Life and Frozen Planet, Watson has developed a unique way of composing with sound that revolves around communicating a “sense and spirit of place.”

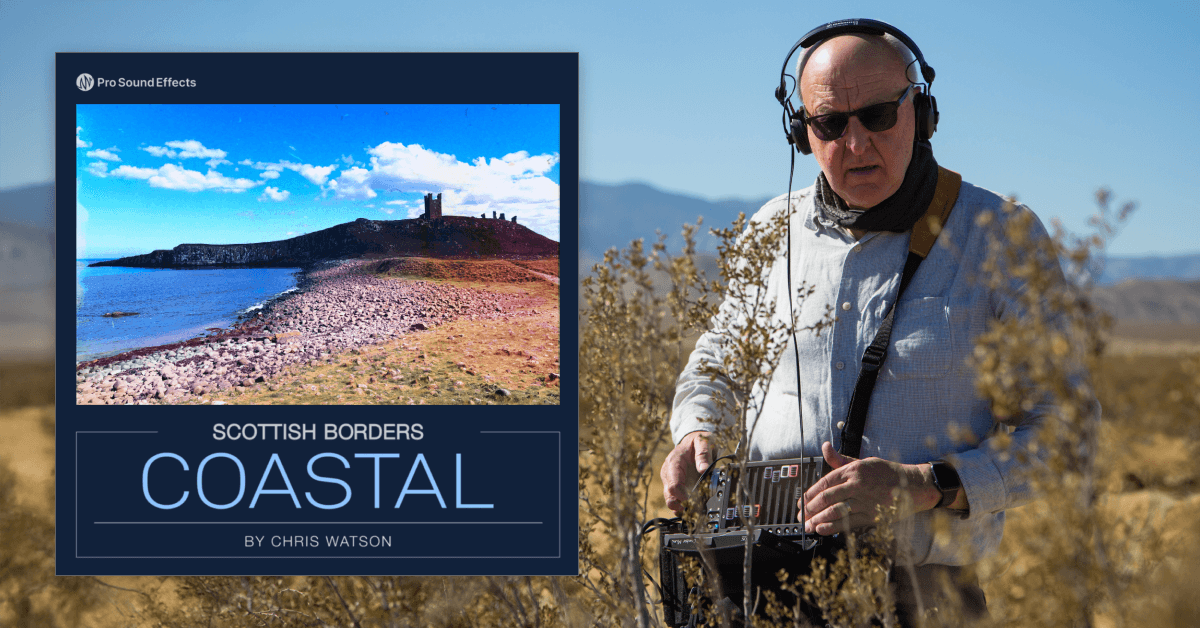

This ethos is perfectly embodied in Watson’s first library release with PSE, Scottish Borders: Coastal. With an artist’s eye and a composer’s ear, Watson has curated a set of recordings that capture the full breadth of the region’s coastal environments. Watson, who recently moved to the Borders, joined us to talk about his background, his approach to field recording, and some of his favorite sounds in the new library.

How did you first become fascinated by sound?

Chris Watson: When I was 12 or 13, my parents bought me this portable reel-to-reel tape recorder, a Japanese machine made by a company called National. I started recording everything in the house: the squeaking doors, the refrigerator, the toilet flushing, the taps, and things like that. And then I realized it had batteries in it, so I could take it outside.

Where I grew up, in the north of England, we had a bird feeder table in the back garden. I went out and put some bird food on the table, hung that recorder underneath, turned it to Record, and left it. I like to think I can remember that moment 50-odd years ago when I brought this little recorder back inside and pressed Play. I can remember being taken to another world: this magical environment where we can never be because our presence would change the behavior of the birds and the animals. It was just this magical moment.

Then, I discovered that I could use it for time-shifting – I could not only capture sounds, but I could play them back at different speeds. I also discovered that I could manipulate the tape itself. It's an analog medium, so you can cut and splice, play things backwards, speed them up, slow them down, and compose with it. It's a very tactile experience and it was a beautiful medium to start to learn to work with sound creatively.

Later on, I discovered musique concrète via BBC Radio and the work of Pierre Schaeffer. He was a French composer in the late 1940s and early 1950s who invented this form of composition by creating music from location sound recordings. Most famously, he used a series of recordings made in a Parisian railway station to compose a work called Étude aux Chemins de Fer (Railway Study). That just blew me away as a teenager.

Discovering that you could use this device not only to document sounds but to work with them creatively really started me on the journey, and that's why I'm speaking to you today.

How has music inspired your field recordings?

My first instrument was a tape recorder, so there was no distinction for me between sound and music. Because I'd been experiencing this idea of creating music from sound recordings – particularly wildlife sounds from the natural world – the two were always one. I'm a strong believer in that.

I think all of our music from all of our cultures around the world comes from people experiencing the sounds of the natural world and either mimicking or singing along to those sounds. The sounds of the natural world are deeply embedded in contemporary music.

Of course, like every teenager, I loved music. I tuned into all sorts of things from all around the UK, Europe, and America; from German experimental music to The Velvet Underground and Motown.

I always knew in the back of my mind that it was a creative process and that sound recording was at its heart, and that sort of embedded my connection. Then, I started to think about how I could use my tape recorder in other areas. I started taking my recordings into the studio and discovering how I could work with those sounds creatively, but still thinking of them as music.

"When I was 12 or 13, my parents bought me this portable reel-to-reel tape recorder, a Japanese machine made by a company called National. I started recording everything in the house: the squeaking doors, the refrigerator..."

Chris Watson's first reel-to-reel tape recorder.

What kinds of creative decisions do you make when recording and curating sounds?

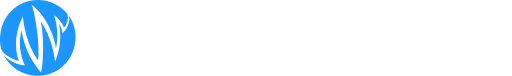

I don't do a lot of unattended recording. I much prefer to be present in the moment. That's the heart of what I do. I really love this idea of a sense and spirit of place, and I believe that's partly embodied by the acoustics of the environment: how the animals behave, how the water sounds, how the wind sounds through certain places.

The older I get, the longer I spend listening and the less time I spend recording. I'm very careful now about pressing Record, because the most crucial thing in any of my work is that original moment. What's important is where I put my microphone before I start to record. I don't just put a microphone out and think I can sort it out in post-production later.

When you're out on location wearing headphones, it's a very visceral and intimate experience, and you can’t share that with anybody. That's why the microphone placement is so important. What I want to do is put the listener at the same place where my microphone was when I made the recording. That's what I enjoy about projects like this – everybody can tune in to the magical sense and spirit of those places and experience it for themselves.

What was your inspiration for creating Scottish Borders: Coastal?

I've had the privilege and luxury of traveling the world with my work, literally from the North Pole to the South Pole and a lot of places in between. It may be something to do with my age, but I'm actually really interested now in exploring the Borders – where we've just moved to – because it is this remarkable mosaic of habitats.

I really love just exploring what's on my doorstep. A lot of the time, people just ignore that. When I was living in the north of England, I just wasn't aware how rich the environment was, because I was traveling the world. What I love about this project is being able to share this sense and spirit of place from somewhere that's just a few yards outside my house.

"What I want to do is put the listener at the same place where my microphone was when I made the recording. That's what I enjoy about projects like this – everybody can tune in to the magical sense and spirit of those places and experience it for themselves."

What’s unique about the Scottish Borders region?

We're very close to the coast and just a few miles away from the river Tweed, which defines the international boundary between Scotland and England. There's a remarkable variety of habitats, from offshore islands to sandy beaches and huge, rocky cliffs. Then, following the river inland to its source in the mountains, there are the habitats in between: the forests, the woodlands, the marshes, the wetlands, the moorlands.

One of the things I enjoy about this place is that you can almost listen back in time because it's relatively unchanged. In terms of evolution, our lifespans are the blink of an eye and our arrival is relatively recent and very transient. All the birds that have been recorded for this library, all the animals, the sound of the ocean, and even the insects were all here thousands of years ago.

There's very little noise pollution here, so I can listen to sounds that people would've experienced centuries ago. For me, that's quite a profound experience. When I'm out there recording I get this really deep sense of connection with the environment and the place.

What makes these recordings different from other nature libraries?

The recordings that I make are deeply personal to me, and I only press Record when I think it's worthwhile. Of course, it's very subjective, but it’s based on a desire to explore with a connection to the history of the place and a respect for the animals as well.

I try not to disturb the things I'm recording, so I often run a hundred or more yards of cable back to a place where I can tune in and listen. Other people may have recorded in the same place, but for me, it's a unique experience and the recordings are very powerful in that sense. What I hope is that this sense and spirit of place is embodied in the recordings and people will be able to experience it when they work with them.

I try to make recordings from varying perspectives. If I'm recording on the coast, I might use directional microphones over the water or hydrophones in rock pools to reveal some of the most astonishing sounds under the surface. Sometimes, I use a parabolic reflector to record individual subjects. Other recordings use spatialized microphone arrays to capture a wide soundfield.

I like the seasonal shifts as well, and that's something that's key to this project. I’ll record in the same place through all four seasons, but also at different times of day, because that's crucial to how the sound evolves in these habitats. A dawn chorus here in May might begin at three o'clock in the morning, but at three in the morning in December, there’ll be this deep sense of quiet and solitude because nothing is singing. You might just hear the occasional howl of a fox or the bark of a deer.

"All the birds that have been recorded for this library, all the animals, the sound of the ocean, and even the insects were all here thousands of years ago."

What uses do you think people will find for these recordings?

I think these recordings are perfect compositional tools, and that's what I use them for. For me, it provides a really rich palette of sounds: ambiences, atmospheres, and featured species recorded from different perspectives and through different types of microphones. It just provides a palette of material for people to work with across lots of different mediums, whether it's film, sound design, or musical composition.

Do you have any favorite recordings or stories from the recording process?

There are some recordings of gray seals singing at night; this beautiful series of haunting voices drifting across the water. When I heard that, I was reminded that it’s the sound of mermaids and sirens that lured sailors onto the rocks centuries ago. To hear that and record it, particularly at night, was really powerful.

The coast in particular has such a long, ancient, and sometimes dark history. In places like Dunstanburgh Castle or Lindisfarne, you get this sense that you're hearing sounds that have been around for millennia. I don't have much hair, but being in those places makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.

Dunstanburgh Castle was built on the English side to protect the border, and it's been there over a thousand years. It’s built on this formation of volcanic rock called dolerite, which is so hard that it doesn't weather, so there are channels in the rocks that were left when the last ice age retreated 10,000 years ago. The sound of the wave wash on those rocks has a very special character.

When the water enters those gullies, it has this really interesting acoustic, almost like a Helmholtz resonator. It has very characteristic sounds depending on the tides, so the sound of the incoming tide is very different from when it ebbs. It has a totally different atmosphere that just shifts your mood, and that's all down to the acoustic of the place.

Dante Fumo is a Midwest-based sound designer, editor, and mixer specializing in independent film and Dolby Atmos mixing. In his free time, Dante composes electronic music and publishes Harmonic Content, a zine about sound.