Explore the creative process behind the dark, moody soundscapes that defined a genre with iconic horror/sci-fi composer and sound designer, Alan Howarth.

As John Carpenter's 1978 classic slasher film Halloween reaches its 40th anniversary this month, horror fans get to celebrate with a new reboot from Universal in theaters as well as a vinyl reissue of the film's timeless score from Mondo and Death Waltz Recording Company. 40 years and ten sequels later, the sonic trademark of the Halloween franchise's early films is undeniable.

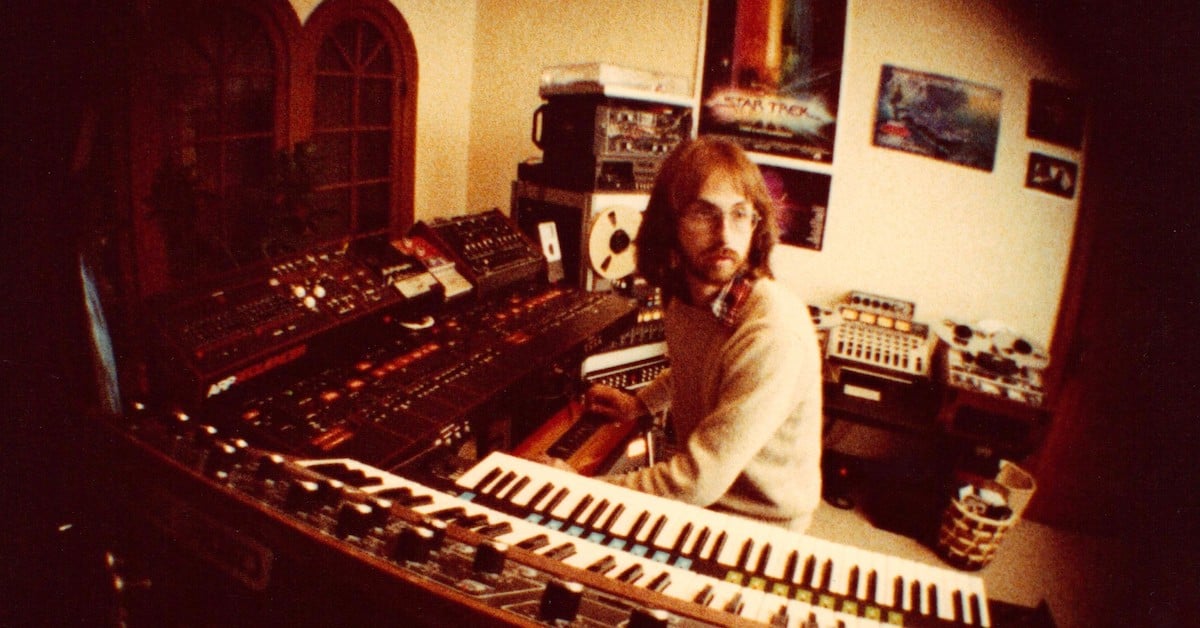

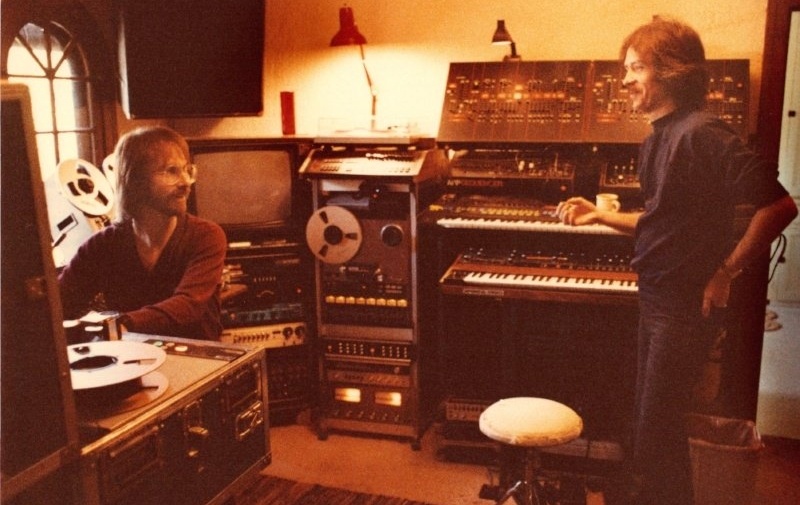

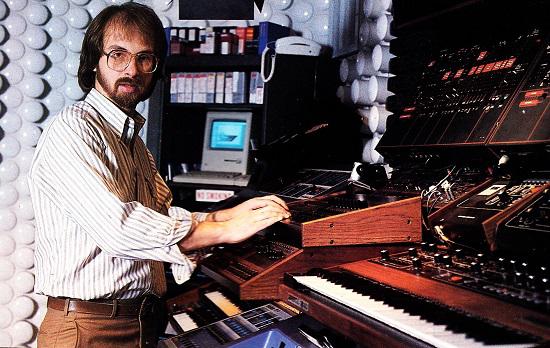

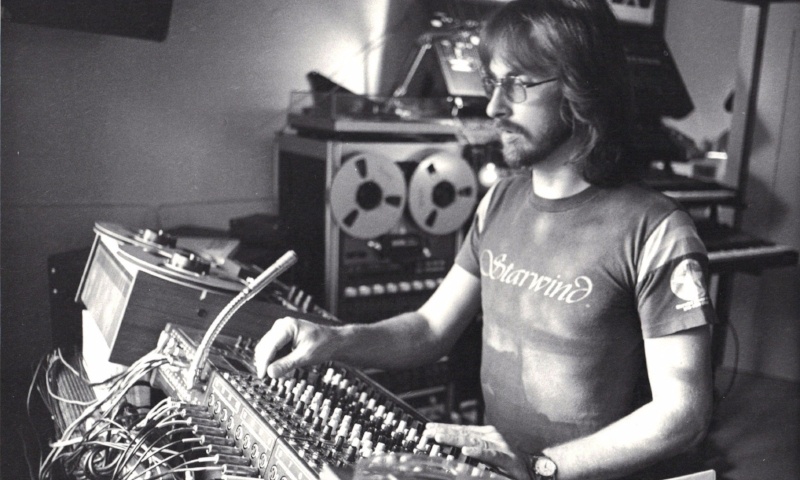

Carpenter – who wrote, directed, and composed the original – enlisted composer and sound designer Alan Howarth to collaborate on the music for Halloween II. Howarth went on to score several Halloween movies through 1995, each time reshaping and expanding Carpenter's original impression. All the while, Howarth established himself as an innovator of horror/sci-fi sound with projects like the original Star Trek films, Poltergeist, Total Recall, and Army of Darkness.

In the spirit of Halloween, our latest sound library Alan Howarth's Cinematic Dread features eerie drones and otherworldly atmospheres crafted by Howarth over decades of pioneering the horror/sci-fi aesthetic. We sat down with Howarth to discuss the legacy of the Halloween films, blurring the lines between music and sound design, sampling air conditioners in the Paramount lot and more. Read our interview below.

PSE: How did your collaboration with John Carpenter on Halloween II come about?

Alan Howarth: After we first worked together on Escape from New York, he basically handed Halloween II off to me because he was busy with The Thing. I got his master recordings from the original film and essentially overdubbed extra textures and layers with synthesizers to add tension and a darker feeling. I did a couple new cues as well. In the Halloween movies that followed I had more and more creative freedom to expand the palette and put my own stamp on it – especially Halloween 4.

What was your usual process and approach for creating the dark drones and atmospheres like those featured in the Cinematic Dread library?

A lot of that stuff was made using analog synths and hybrid synths, like the Prophet VS, which had digital oscillators but analog processing. Other parts were made using samples. Looking for those scrapey, weird, dark tones that could be looped or sustained and manipulated. A couple of the "vortex" sounds in the library are made either from wind or an abrasion of some sort which are then looped and performed. You don't just hold one key down and let it play, at least for me. You can, for sure, but the idea was to put it into a keyboard and use those to perform with, almost like musical tones.

So in the case of something like wind, there's the performance of the sound effects in the track that you get. Slow envelopes in, slow envelopes out. It's being totally manipulated and textured, just like music, but with sounds. One of my strengths was being the crosspiece between music and sound design.

Since your process and results are so musical, do you see a line between sound design and music when you work?

Well, for me, ever since the first Star Trek movies, and all those Carpenter films, you're sitting at the same instrument. It's a musical instrument, and I was asked to use those to make sound effect-y textures using these instruments.

It's interesting – the most basic definition of music is the alternation of sound and silence. Any texture, it's still music to me. When I do my soundtracks, sound design-wise, I'm very conscious about tuning all my sound effects. I remember calling up [composer] James Honer and having discussions about what key a particular piece is in so I would make sure that my tonalities were either in contrast to that, so it wouldn't just blend in, or it was a stack of tones that would sit underneath the score.

"One of my strengths was being the crosspiece between music and sound design... The most basic definition of music is the alternation of sound and silence. Any texture, it's still music to me."

Can you share stories behind a couple specific sounds from the Cinematic Dread library?

So these are wind samples, like I mentioned before. It's very tricky to find wind, because wind doesn't make any sound. It's the wind blowing around something that produces the sound. And the problem is always how do you get wind without all the other stuff on it. I believe the source recordings were made with some wind through chicken wire. We had chicken wire at the mouth of a cave near Vasquez Rocks in Southern California so that we could isolate everything.

This wind through chicken wire gave me a nice tonal kind of thing. And then with those sampled and put in the keyboard, it becomes a musical performance. The rising and the falling of the intensity of the wind is just performance on the keyboard, from the lower notes to the higher notes, and putting them into long envelopes with long releases, so you start playing and things hang in there. Just imagining the scene in my mind with things hanging low, swelling, and creating an atmosphere.

That's actually done from an air conditioner. There was this one room on a Paramount lot – it was behind one of the sound stages. They have these huge air conditioning things, and there was one place that had this huge acoustical low-end... I remember it was called Room 13. So I recorded that and then played it through a spring reverb to stretch it mechanically instead of digitally.

In what way do you think your process informed your results and what came to be your sound?

Sometimes the restriction of the technology makes you do more with what you've got, instead of just having everything. You had to originate it. By doing that kind of origination, it gives that particular soundtrack a special uniqueness.

Most of this stuff was created because I was in a movie that needed the sounds. It didn't exist at the time, so we had to go out and figure it out – whether it was scraping around in some weird piece of metal, or finding a cave, or smashing up rocks in the middle of the studio floor and slowing it way down to make big rocks out of bricks... things like that. It was all experimentation and manipulation. But the technique that we came up with was the foundation. That's what you do and how you do it.

What will sound artists achieve by using these sounds in their projects?

One of my main functions in Hollywood was to make things that didn't exist. There was always some new image, some new monster, some new quality, some new desolate place that needed atmosphere. A lot of these sounds are really useful for spaceships, or outer space somewhere, or some strange structure or evil place.

The idea of giving a title to a family of sounds, and calling it Cinematic Dread, is helpful when you think, "I need a droney, dark, thing. Oh, Alan Howarth did all that stuff, we'll go and get his stuff." And there it is, all the hours of sitting in a dark room trying to figure it out. A lot of the hard work is done. The editor goes through and makes a palette out of what's there, and there you go. That's what's so great about your libraries. It's like my colleagues, Richard L. Anderson and Mark Mangini, and what you’re doing with their library sounds for the Odyssey Collection. We were all on the first Star Trek movie in 1979. And here we are 40 years later.

And we're under such deadlines now too. There's some amazing sound design work being done now by all these folks in the business. Projects today are calling for as much soundscape bandwidth as a full feature film with ten people that had six weeks to do it. And now you've got to pull it off in a week. When you're the sound person, everybody has already blown the budget and are coming in late, and the delivery didn't change. You're always the last one who has to hurry up and get it done, because everybody else messed up the schedule. You have to function under that pressure.

"Sometimes the restriction of the technology makes you do more with what you've got, instead of just having everything. You had to originate it. By doing that kind of origination, it gives that particular soundtrack a special uniqueness."

Why do you think your work has made such a lasting impression on creators of other films and shows over the years – including today?

A lot of these sounds are so organic. The project always wanted stuff to seem like it came from reality, even though it was all twisted and turned and moved around. Whereas just straight oscillator boops and beeps and such were fine if it was electronic, but to make these things believable, they can feel like they come from these weird spaces, these weird environments, these strange atmospheres. I put a lot of time into creating stuff like that.

I guess the word would be "resonance." People can relate to it. I mean especially the stuff I do with John Carpenter. Look at Stranger Things. Those guys are redoing what we did then. That was the good stuff, let's just keep doing it like that.

If you look at my filmography, you'll see the nature of the body of films that I worked on. Poltergeist, Raiders, The Hunt for Red October, Dracula, Total Recall... these are all titles that were science fiction, futuristic things from that time, and a lot of modern stuff. The point is, it still holds up. I'm amazed that we even care about this right now. So much stuff is just a trash bin already. I didn't think about it at the time. I just did it because I was an artist.

Available Now – Alan Howarth's Cinematic Dread